Japanese History and the Oregon Megaquake of 1700

A mere quarter century ago, scientists doubted there was any earthquake risk posed by the Cascadia Subduction Zone, the meeting place of two tectonic plates 50 to 75 miles off the Oregon coast. In a few short years, however, Oregonians have become aware that a devastating megaquake is likely to occur in our lifetimes or in the lives of our children. It was 312 years ago, on January 26, 1700. that our region experienced the last huge earthquake, estimated as a magnitude 9.0 in the Richter Scale. “In geologic terms, says Yumei Wang of the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, Cascadia’s next quake is “9 months pregnant”,

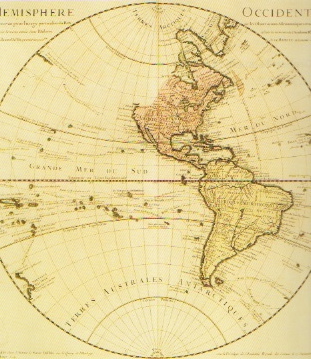

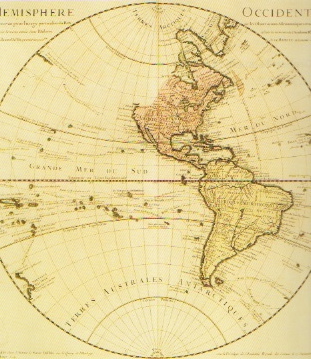

How is it that geologists now speak with such certainty? How is it that they’ve suddenly been able to track earthquakes occurring about every 250 years over the past 10,000 years? After all, the geography of the Pacific Northwest was unknown to outsiders in 1700, as seen in this period map. It would be another 78 years before Captain Cook, and more than 90 before the arrivals of George Vancouver, Robert Gray and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra.

The Orphan Tsunami of 1700: Japanese Clues to a Parent Earthquake in North America recounts the fascinating story of recent geological and archaeological sleuthing coupled with the fine work of early 18th century Japanese scholars, artists and scribes. In the mid 1980s a young geologist named Brian Atwater stumbled on dead cedar trees in a marsh and wondered if they’d been downed in an earthquake. Changes in soil character, layers, and plant remains along the 700 kilometers of coast from Washington State to Northern California was the evidence he pieced together to narrow the window of the cataclysm to between 1695 and 1720. Then in the mid 1990s researchers in Japan published a paper on a tsunami which struck there in 1700. After learning Japanese, Atwater headed to Japan to join fellow authors of the story they called “the orphan tsunami of the Genroku era”.

The profusely illustrated slim volume is an arresting look at impact of earthquakes and tsunamis on both sides of the Pacific. For North America, the authors provide flood stories of native groups from Cape Flattery to Nootka Sound, ariel photos of Alaskan rivers flowing upstream, the sunken shores of Washington State’s Willapa Bay and the Copalis River, silted up forests of trees whose rings indicate sudden death, buried marsh soils and native fire pits far below the surface.

How is it that geologists now speak with such certainty? How is it that they’ve suddenly been able to track earthquakes occurring about every 250 years over the past 10,000 years? After all, the geography of the Pacific Northwest was unknown to outsiders in 1700, as seen in this period map. It would be another 78 years before Captain Cook, and more than 90 before the arrivals of George Vancouver, Robert Gray and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra.

The Orphan Tsunami of 1700: Japanese Clues to a Parent Earthquake in North America recounts the fascinating story of recent geological and archaeological sleuthing coupled with the fine work of early 18th century Japanese scholars, artists and scribes. In the mid 1980s a young geologist named Brian Atwater stumbled on dead cedar trees in a marsh and wondered if they’d been downed in an earthquake. Changes in soil character, layers, and plant remains along the 700 kilometers of coast from Washington State to Northern California was the evidence he pieced together to narrow the window of the cataclysm to between 1695 and 1720. Then in the mid 1990s researchers in Japan published a paper on a tsunami which struck there in 1700. After learning Japanese, Atwater headed to Japan to join fellow authors of the story they called “the orphan tsunami of the Genroku era”.

The profusely illustrated slim volume is an arresting look at impact of earthquakes and tsunamis on both sides of the Pacific. For North America, the authors provide flood stories of native groups from Cape Flattery to Nootka Sound, ariel photos of Alaskan rivers flowing upstream, the sunken shores of Washington State’s Willapa Bay and the Copalis River, silted up forests of trees whose rings indicate sudden death, buried marsh soils and native fire pits far below the surface.

On the other side of the Pacific, evidence of the orphan tsunami had been building up for centuries. Maps before and after 1700 show radically altered shorelines. A delicate drawing of the village of Miho shows waves surrounding the pine trees on the sandspit protecting the harbor and surmounting the coastal road with Mt. Fuji in the background. There were accounts of crops destroyed, warehouses flooded, marine shipments lost, sailors drowned, large quantities of wood ordered for new houses. Village headmen, merchants, samurai, fishermen and peasants from towns north and south of present day Tokyo left dozens of documents which by the early 1990s pointed a well-documented tsunami of unknown origin.

An earthquake of magnitude of 9.0 “radiates as much energy as the United States consumes in a month, or twice the energy a hurricane’s winds would release if they blew nonstop for a month.” (p. 98). In the past century, only the 1960 Chile and 1964 Alaska quakes surpassed 9.0 but the 1700 Cascadia Quake is thought to have been of comparable magnitude. The rupture along the coast was 1100 km in length and 100 km wide and contemporary GPS measurements have enable simulations of plate movements and sea-floor thrust. Similarly, simulations based on Japanese data for high-water damage and contours of flooding in 1700 rule out a quake of a lower magnitude.

The 1700 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake is now firmly documented by the United States Geologic Survey, as well as by Natural Resources Canada. The entire, full-color, 144-page book The Orphan Tsunami of 1700, also known as Professional Paper 1707, can be downloaded free from the USGS website.

On the other side of the Pacific, evidence of the orphan tsunami had been building up for centuries. Maps before and after 1700 show radically altered shorelines. A delicate drawing of the village of Miho shows waves surrounding the pine trees on the sandspit protecting the harbor and surmounting the coastal road with Mt. Fuji in the background. There were accounts of crops destroyed, warehouses flooded, marine shipments lost, sailors drowned, large quantities of wood ordered for new houses. Village headmen, merchants, samurai, fishermen and peasants from towns north and south of present day Tokyo left dozens of documents which by the early 1990s pointed a well-documented tsunami of unknown origin.

An earthquake of magnitude of 9.0 “radiates as much energy as the United States consumes in a month, or twice the energy a hurricane’s winds would release if they blew nonstop for a month.” (p. 98). In the past century, only the 1960 Chile and 1964 Alaska quakes surpassed 9.0 but the 1700 Cascadia Quake is thought to have been of comparable magnitude. The rupture along the coast was 1100 km in length and 100 km wide and contemporary GPS measurements have enable simulations of plate movements and sea-floor thrust. Similarly, simulations based on Japanese data for high-water damage and contours of flooding in 1700 rule out a quake of a lower magnitude.

The 1700 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake is now firmly documented by the United States Geologic Survey, as well as by Natural Resources Canada. The entire, full-color, 144-page book The Orphan Tsunami of 1700, also known as Professional Paper 1707, can be downloaded free from the USGS website.

How is it that geologists now speak with such certainty? How is it that they’ve suddenly been able to track earthquakes occurring about every 250 years over the past 10,000 years? After all, the geography of the Pacific Northwest was unknown to outsiders in 1700, as seen in this period map. It would be another 78 years before Captain Cook, and more than 90 before the arrivals of George Vancouver, Robert Gray and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra.

The Orphan Tsunami of 1700: Japanese Clues to a Parent Earthquake in North America recounts the fascinating story of recent geological and archaeological sleuthing coupled with the fine work of early 18th century Japanese scholars, artists and scribes. In the mid 1980s a young geologist named Brian Atwater stumbled on dead cedar trees in a marsh and wondered if they’d been downed in an earthquake. Changes in soil character, layers, and plant remains along the 700 kilometers of coast from Washington State to Northern California was the evidence he pieced together to narrow the window of the cataclysm to between 1695 and 1720. Then in the mid 1990s researchers in Japan published a paper on a tsunami which struck there in 1700. After learning Japanese, Atwater headed to Japan to join fellow authors of the story they called “the orphan tsunami of the Genroku era”.

The profusely illustrated slim volume is an arresting look at impact of earthquakes and tsunamis on both sides of the Pacific. For North America, the authors provide flood stories of native groups from Cape Flattery to Nootka Sound, ariel photos of Alaskan rivers flowing upstream, the sunken shores of Washington State’s Willapa Bay and the Copalis River, silted up forests of trees whose rings indicate sudden death, buried marsh soils and native fire pits far below the surface.

How is it that geologists now speak with such certainty? How is it that they’ve suddenly been able to track earthquakes occurring about every 250 years over the past 10,000 years? After all, the geography of the Pacific Northwest was unknown to outsiders in 1700, as seen in this period map. It would be another 78 years before Captain Cook, and more than 90 before the arrivals of George Vancouver, Robert Gray and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra.

The Orphan Tsunami of 1700: Japanese Clues to a Parent Earthquake in North America recounts the fascinating story of recent geological and archaeological sleuthing coupled with the fine work of early 18th century Japanese scholars, artists and scribes. In the mid 1980s a young geologist named Brian Atwater stumbled on dead cedar trees in a marsh and wondered if they’d been downed in an earthquake. Changes in soil character, layers, and plant remains along the 700 kilometers of coast from Washington State to Northern California was the evidence he pieced together to narrow the window of the cataclysm to between 1695 and 1720. Then in the mid 1990s researchers in Japan published a paper on a tsunami which struck there in 1700. After learning Japanese, Atwater headed to Japan to join fellow authors of the story they called “the orphan tsunami of the Genroku era”.

The profusely illustrated slim volume is an arresting look at impact of earthquakes and tsunamis on both sides of the Pacific. For North America, the authors provide flood stories of native groups from Cape Flattery to Nootka Sound, ariel photos of Alaskan rivers flowing upstream, the sunken shores of Washington State’s Willapa Bay and the Copalis River, silted up forests of trees whose rings indicate sudden death, buried marsh soils and native fire pits far below the surface.

On the other side of the Pacific, evidence of the orphan tsunami had been building up for centuries. Maps before and after 1700 show radically altered shorelines. A delicate drawing of the village of Miho shows waves surrounding the pine trees on the sandspit protecting the harbor and surmounting the coastal road with Mt. Fuji in the background. There were accounts of crops destroyed, warehouses flooded, marine shipments lost, sailors drowned, large quantities of wood ordered for new houses. Village headmen, merchants, samurai, fishermen and peasants from towns north and south of present day Tokyo left dozens of documents which by the early 1990s pointed a well-documented tsunami of unknown origin.

An earthquake of magnitude of 9.0 “radiates as much energy as the United States consumes in a month, or twice the energy a hurricane’s winds would release if they blew nonstop for a month.” (p. 98). In the past century, only the 1960 Chile and 1964 Alaska quakes surpassed 9.0 but the 1700 Cascadia Quake is thought to have been of comparable magnitude. The rupture along the coast was 1100 km in length and 100 km wide and contemporary GPS measurements have enable simulations of plate movements and sea-floor thrust. Similarly, simulations based on Japanese data for high-water damage and contours of flooding in 1700 rule out a quake of a lower magnitude.

The 1700 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake is now firmly documented by the United States Geologic Survey, as well as by Natural Resources Canada. The entire, full-color, 144-page book The Orphan Tsunami of 1700, also known as Professional Paper 1707, can be downloaded free from the USGS website.

On the other side of the Pacific, evidence of the orphan tsunami had been building up for centuries. Maps before and after 1700 show radically altered shorelines. A delicate drawing of the village of Miho shows waves surrounding the pine trees on the sandspit protecting the harbor and surmounting the coastal road with Mt. Fuji in the background. There were accounts of crops destroyed, warehouses flooded, marine shipments lost, sailors drowned, large quantities of wood ordered for new houses. Village headmen, merchants, samurai, fishermen and peasants from towns north and south of present day Tokyo left dozens of documents which by the early 1990s pointed a well-documented tsunami of unknown origin.

An earthquake of magnitude of 9.0 “radiates as much energy as the United States consumes in a month, or twice the energy a hurricane’s winds would release if they blew nonstop for a month.” (p. 98). In the past century, only the 1960 Chile and 1964 Alaska quakes surpassed 9.0 but the 1700 Cascadia Quake is thought to have been of comparable magnitude. The rupture along the coast was 1100 km in length and 100 km wide and contemporary GPS measurements have enable simulations of plate movements and sea-floor thrust. Similarly, simulations based on Japanese data for high-water damage and contours of flooding in 1700 rule out a quake of a lower magnitude.

The 1700 Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake is now firmly documented by the United States Geologic Survey, as well as by Natural Resources Canada. The entire, full-color, 144-page book The Orphan Tsunami of 1700, also known as Professional Paper 1707, can be downloaded free from the USGS website.